In the early 20th century the southern part of El Raval was referred to as barrio chino – Chinatown – even though it had no Chinese connections. The barrio was infamous for its poverty, violence and deprivation. Legend says the local journalist Francesc Madrid saw a movie about vice in San Francisco's Chinatown and adopted the name for the "underworld centre" of Barcelona. El Raval has always been a poor district, being the heart of Catalan industrialization and a typical working class neighbourhood. Located right next to the port and just outside the old city wall, there has always been business connected with sex, drugs and taverns, which has led to all kinds of myths associated with the barrio (1).

Starting in the late 1980s, following a steep rise in the use of heroin in the barrio, the Ajuntament de Barcelona – the municipality – actively tried to rebrand El Raval as a culturally vibrant district, changing the physical appearance of the neighbourhood and introducing new institutions. Even though the purpose was to rebrand the neighbourhood in preparation for the Olympic Games in 1992, these processes continued afterwards (8).

The Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) were built in northern El Raval in the 1990s. Over 1,300 houses were demolished in southern El Raval in order to create a tree-lined pedestrian zone. Today this is known as the Rambla del Raval, and is used as a meeting space by residents. It also serves as a tourist attraction with various restaurants, and is home to the symbol of the district: the famous gato de botero, a big iron cat (2). These top-down processes triggered various developments with both positive and negative consequences for the barrio, and a lot of them are connected to tourism.

On the one hand, El Raval became famous for its culturally active “alternative” scene, which is centred around sprayers, skaters and dancers at MACBA. This brought in tourists looking for an “alternative” Barcelona, and higher income classes, which led to a lot of private investments in the district. New income opportunities arose for the residents.

On the other hand, rents and prices are still rising, and speculation with flats has become a serious issue. Tourist apartments like Airbnb are now further exacerbating problems in the already tight housing market. More and more inhabitants are being forced to move out of the neighbourhood because of the prices, a typical gentrification process. Furthermore, consumption opportunities are targeted towards tourist needs, crime rates have gone up (5), and parties of tourists are adding to the stress of inhabitants due to increasing noise. The barrio has changed rapidly over the course of the past thirty years, with tourism becoming one of its driving factors. How can El Raval and its inhabitants deal with these challenges triggered by tourism? How do these transformations and different reactions to them manifest themselves within the district?

El Raval

Between economic development and resistance

This is El Raval

As mentioned by Gerardo Etturi – Tour Guide of “Uncensored Tours” in El Raval – the district is divided into two parts:

- A north-eastern part, Upper Raval, which is characterized by high-price shops, expensive bars, “hipsters”, and high rents. Consumption opportunities are targeted towards tourists. The cultural and public institutions are mostly located here. Tourism can be considered the driving factor of this neighbourhood.

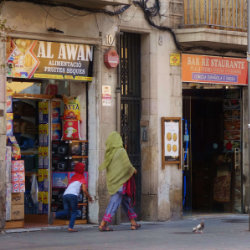

- A south-western part, Lower Raval, which is less expensive. Here, the shops are targeted more towards the local population. The streets in general feel less influenced by tourism.

This division of the district into two parts does not hold true on every corner or street, but it represents a noticeable tendency. While there are some expensive shops and bars in Lower Raval, you can encounter streets without any kind of shop or restaurant when walking through Upper Raval. The eastern border of Upper Raval is La Rambla, not to be confused with Rambla del Raval. La Rambla is the most highly frequented street in Barcelona, leading cruise tourists into the inner city. This heavily influences tourism in El Raval and partially explains why there is a felt bisection of the barrio. Generally, the closer to La Rambla, the more touristified the surroundings will be.

Another noticeable trend concerns the direction of the streets. Those going west from La Rambla, directly into the district, are heavily touristified, with restaurants offering sangria and paella – food perceived as being typically local – and advertising in English. The streets going south-north, parallel to La Rambla, feel completely different: sometimes they seem untouched by the touristic boom, sometimes they seem completely abandoned, and sometimes they have a special character. This can lead to surprising walking experiences where you go around a corner and your surroundings change completely. This is most memorable at the place where La Carrer de l’Hospital crosses La Carrer de’En Robador. The shop on the corner offers high-price vintage leather, while in the street next to it women offer their bodies – the “street of thieves” is historically famous for street prostitution. As Anton, who has lived in El Raval for four years, explains: “Raval was a dangerous neighbourhood; now it’s a touristy and dangerous neighbourhood.”

Another noticeable trend concerns the direction of the streets. Those going west from La Rambla, directly into the district, are heavily touristified, with restaurants offering sangria and paella – food perceived as being typically local – and advertising in English. The streets going south-north, parallel to La Rambla, feel completely different: sometimes they seem untouched by the touristic boom, sometimes they seem completely abandoned, and sometimes they have a special character. This can lead to surprising walking experiences where you go around a corner and your surroundings change completely. This is most memorable at the place where La Carrer de l’Hospital crosses La Carrer de’En Robador. The shop on the corner offers high-price vintage leather, while in the street next to it women offer their bodies – the “street of thieves” is historically famous for street prostitution. As Anton, who has lived in El Raval for four years, explains: “Raval was a dangerous neighbourhood; now it’s a touristy and dangerous neighbourhood.”

The described diversity and heterogeneity of the barrio are shown in the pictures below. When walking through El Raval you will probably experience similar impressions.

El Raval and its criminality

It is impossible to write about the different aspects of El Raval without discussing its criminal connections. The overall discourse on today's El Raval is heavily influenced by the past of the barrio and its representation in the media. There are certain topics that appear to define the primary discourse on this district, all circling around its perceived wickedness: poverty, drugs and prostitution.

How can we describe a neighbourhood and its criminality without either making it more criminal than it actually is, or implicitly denying its criminality through academic discussions of the “construction of a criminal district”?

This is even more complicated in the case of El Raval, as there are no official crime statistics just for the barrio. Generally, in statistics prepared by the municipal authorities, El Raval appears as a part of Ciutat Vella, the old town, which also includes Barri Gòtic, La Barceloneta and Sant Pere. This makes the statistics useless if the goal is to discuss criminality on barrio level. Nevertheless, Ciutat Vella as a whole has the highest number of reported crimes per inhabitant in Barcelona (18). In 2016 this number was 86 crimes per 100 inhabitants; in 2017 it increased to 122 (3), and in 2018 (4) it rose to 191 crimes per 100 inhabitants.

A first assumption concerning the relationship between tourism and criminality is that tourism leads to a decline in criminality. This does not hold true in this case. Ciutat Vella, which is the most touristified area of Barcelona, also has the highest density of criminal activities. The high crime rates are mostly a result of tourism, since the commonest crimes are pickpocketing and robbery on the streets – so called petty crime – where the targets are mostly tourists. Out of 44,241 crimes in Ciutat Vella in 2017, only 31 were murders or homicides (5, 6, 7). David S., a resident and member of a neighbourhood association in El Raval, explains that residents suffer as a secondary effect. Tourists attract criminals, who then also commit crimes against residents. Such a burglary is described by Teresa, an elderly woman who owns a shop in El Raval.

How can we describe a neighbourhood and its criminality without either making it more criminal than it actually is, or implicitly denying its criminality through academic discussions of the “construction of a criminal district”?

This is even more complicated in the case of El Raval, as there are no official crime statistics just for the barrio. Generally, in statistics prepared by the municipal authorities, El Raval appears as a part of Ciutat Vella, the old town, which also includes Barri Gòtic, La Barceloneta and Sant Pere. This makes the statistics useless if the goal is to discuss criminality on barrio level. Nevertheless, Ciutat Vella as a whole has the highest number of reported crimes per inhabitant in Barcelona (18). In 2016 this number was 86 crimes per 100 inhabitants; in 2017 it increased to 122 (3), and in 2018 (4) it rose to 191 crimes per 100 inhabitants.

A first assumption concerning the relationship between tourism and criminality is that tourism leads to a decline in criminality. This does not hold true in this case. Ciutat Vella, which is the most touristified area of Barcelona, also has the highest density of criminal activities. The high crime rates are mostly a result of tourism, since the commonest crimes are pickpocketing and robbery on the streets – so called petty crime – where the targets are mostly tourists. Out of 44,241 crimes in Ciutat Vella in 2017, only 31 were murders or homicides (5, 6, 7). David S., a resident and member of a neighbourhood association in El Raval, explains that residents suffer as a secondary effect. Tourists attract criminals, who then also commit crimes against residents. Such a burglary is described by Teresa, an elderly woman who owns a shop in El Raval.

What residents have to say about criminality

Nearly everyone in the barrio has something to say about criminality and their perceptions of it vary greatly. In general, the rising crime rates have led to a feeling of insecurity. Residents of Barcelona feel more unsafe than at any other time during the past two decades, which corresponds to perceptions of safety in El Raval (18). This has led to demonstrations demanding more police and tighter controls. The socialization of individuals is a big factor in perceptions of how dangerous the barrio is.

Simón, a street vendor from Chile, tells us that El Raval is certainly rough, but it is nowhere near as dangerous as big cities in Latin America. Anton, a German immigrant, does not visit bars in El Raval at night, but he does go to bars in other districts, because he feels he cannot “relax” in El Raval. Pedro, a resident who was born in El Raval, says that there is crime, mafia, prostitution everywhere in the barrio. Thus, there is no objective answer to the question of safety in the barrio. People’s perceptions are very different because the “locals” are in fact very diverse.

Simón, a street vendor from Chile, tells us that El Raval is certainly rough, but it is nowhere near as dangerous as big cities in Latin America. Anton, a German immigrant, does not visit bars in El Raval at night, but he does go to bars in other districts, because he feels he cannot “relax” in El Raval. Pedro, a resident who was born in El Raval, says that there is crime, mafia, prostitution everywhere in the barrio. Thus, there is no objective answer to the question of safety in the barrio. People’s perceptions are very different because the “locals” are in fact very diverse.

Who is a local and who is a tourist?

But of the three individuals we have quoted, who is a “local”? Is it only Pedro, who was born and raised in El Raval? Anton explains that a typical problem he has is the availability of everyday objects like shoe polish, because the shops mostly sell things like sparkling wine, other alcoholic drinks and potato chips. He has to drive far for his daily needs. His problems are those of a local, even though he may not be perceived as one. People tend to speak English to him at first, even though he speaks perfect Spanish. This relationship between locality and tourism becomes apparent around MACBA.

The museum of modern art is an attraction for culturally interested visitors. It is a place passed through by many parents picking up their children from school and it is one of Barcelona’s hot spots for (international) skaters. At night it is a popular meeting place to drink and be with friends. The space in front of MACBA is used by many different groups, which has led to increasing conflict. “You cannot skate at night as it’s not allowed between 10pm and 7am”, says an official sign. A message painted on the ground says: “You can be dangerous, remember that pedestrians always have right of way”, or “Skateboarding is noisy, so get around the streets of El Raval on foot”.

Pedestrians can be tourists, they can be residents. When walking past MACBA, both might feel equally disturbed by skaters. The skaters themselves can also be tourists or residents: “Just don’t interrupt me while I’m skating. Take your photos, but don’t get me off my board”, says a female skater from Australia, when asked if she would agree to an interview. The woman wants to enjoy Barcelona’s skater scene and has come to Barcelona as a tourist, but she feels like a local in El Raval and in the everyday activities around MACBA. By her presence, she simultaneously plays a role in a neighbourhood conflict and reproduces an international, open skating scene which again attracts more skateboard tourists.

El Raval does not attract mass tourism. There are no “must-sees” like the Sagrada Familia in the district. Tourists visiting El Raval are either there due to the district’s proximity to La Rambla or because they hope for real, authentic experiences, specifically visiting the district for this purpose (19). This type of tourism is called “new urban tourism” (10) or “off-the-beaten-track tourism” (14). The aim is to “live like a local”, staying in apartments within the district to share and experience the everyday life of locals. When investigating the production of urban spaces, it is crucial to dissociate oneself from typification, because the characteristics of locals and tourists can be discussed as “performative” (21). A person can be in several inherent positions. Tourists may sit in community gardens, lie on benches covered with graffiti, and drink, skate and spray with the local youth, while local residents may drink craft beer and soja lattes in bars and cafés that were originally built for tourists, thus practising the “touristification of everyday life” (16). Tourism researcher Robert Maitland summarizes this as follows: “Tourism itself cannot any longer be bounded off as a separate activity, […] and tourist demands cannot be clearly separated from those of residents and other users of the city” (12).

This picture of tourists and locals demanding the same products does not always add up in reality. There are certain products which are requested more by tourists than residents which leads to the construction of certain types of shops and restaurants that are mostly used by tourists. There are not enough residents in El Raval to eat the amount of offered paellas. Somebody who tries to act local for the most part of their travels might still buy a souvenir at the end of the vacation. Even if he or she only visits bars normally visited by locals, it will always change the offers: They will become more expensive. Through their presence tourists are creating visible, materialized changes in the city: This process is referred to as bottom-up touristification (11).

How tourism affects shops and restaurants

One can argue that an “authentic tourism experience” is a contradiction in itself. Places that are visited by tourists are changed by the demands of the tourists themselves and by the economic opportunities this presents for the providers. This can ultimately lead to disneyfication, a process where the whole infrastructure of a city is aimed at creating consumption opportunities, in this case for tourists (15).

There can only be so many people looking for an original Barcelona, for at some point they become the experience. Other parts of Ciutat Vella like El Born already feel like a tourist theme park of Barcelona, because tourists share the daily life not of local inhabitants but of other tourists. As tourism and its industry steadily grows in Barcelona and El Raval, resistance against it rises as well.

There can only be so many people looking for an original Barcelona, for at some point they become the experience. Other parts of Ciutat Vella like El Born already feel like a tourist theme park of Barcelona, because tourists share the daily life not of local inhabitants but of other tourists. As tourism and its industry steadily grows in Barcelona and El Raval, resistance against it rises as well.

El Raval in resistance

In El Raval you quickly notice a politically tense climate alongside normal big city life. White banners hang from narrow, barred balconies. “ENOUGH!” they say in Catalan, written in big black and red letters. “Real estate speculation is driving us out of the quarter (“PROU!! Especulació immobiliária que ens fa fora del barri!”). The group behind this is Guerilla Raval, an organized group of women, who are responsible for most of the protest banners in El Raval. In public and on Twitter (13) they point out disaffection over real estate speculation, and its consequences for individuals and families. One of the effects of trying to become a part of the barrio in a “new urban tourist” way is the further pressure that it puts on the housing market: the inhabitants have to compete not just with each other but also with tourists. This is especially critical in a neighbourhood which is already attracting higher income classes in comparison to its originally poor residents. Prices per square metre rose from 11.10 € in 2015 to 14.02 € in 2018 in El Raval (20). Data collection started in 2015. Airbnb prices per night range from around 30 euros to 80 euros per night for single bedrooms, depending on the season and time of booking (17). As a landlord you can earn a lot more with tourists than with residents, because only richer residents can cope with the rising rents.

In Raval there are multiple activists and groups. This district was a hotbed of activism and anarchism at the beginning of the 20th century (9). If you were to look for the heart of Barcelona’s activist scene today, it would be in El Raval. One of the centres of resistance is El Lokal, a small anarchist bookstore.

“We have four evictions today”, says Iñaki García, activist and founding member of “El Lokal”. Today, he and other confederates will try to save the homes of four families. “They were not able to pay the rent anymore. The rents are more expensive, housing is used by investors, to implement more and more Airbnb apartments. This happens almost everywhere in Barcelona. People are thrown out of their apartments; thus, the apartments are empty until they get rebuilt.”

“We have four evictions today”, says Iñaki García, activist and founding member of “El Lokal”. Today, he and other confederates will try to save the homes of four families. “They were not able to pay the rent anymore. The rents are more expensive, housing is used by investors, to implement more and more Airbnb apartments. This happens almost everywhere in Barcelona. People are thrown out of their apartments; thus, the apartments are empty until they get rebuilt.”

El Raval in resistance

A few blocks away, in Lower Raval, residents try to create spots unaffected by globalization. Amid run-down but inhabited residential blocks, an urban gardening project is located. Every visitor is invited to contribute to the garden, for example with new graffiti or new plants. Looking around, it can be seen that there was once a block of flats here and that the garden was created on demolition waste. First, it was planned to build a school here, but bureaucracy and lack of money resulted in a ten years building freeze and after so many years it got littered with rubbish. In general, residents feel left alone with their problems by the municipal authorities. Julio, one of the interviewees sits on a metal chair in front of a colourfully painted background. “My neighbour Flora had the idea of making the garden”, he says. “One day, she saw rats running about and she decided would no longer put up with the situation.”

The garden shows the absurdity of the power of the tourism industry over basic needs of the population. While there was no money for a school at this place, and it took the city over ten years to decide what to do with the site, residents took action to fill the place with life. Meanwhile, two blocks away, at la Rambla del Raval, a huge luxury hotel was built.

El Raval attacked by globalisation

The picture above, which is a wall painting in a community garden in El Raval, shows criticism of urban development in Barcelona in a creative way. It shows the barrio as an old tree that is attacked by different faces of globalization. Tourism – shown for example by an almost overflowing “I love BCN” cup – is only one of them.

To summarize, a lot of people in El Raval do not necessarily blame tourism itself for injustices and displacements. Protests usually target the organization of tourism in the neighbourhood, especially speculation with flats and Airbnbs that lead to the displacement of residents. As Iñaki García puts it, it is the “industry of tourism” that is responsible for those injustices. Resistance against this industry is especially difficult as it is not just located in El Raval, it is embedded in a globalized context. When Iñaki says that low-cost flights should be stopped, in order to create a tourism that works for the city, this shows two things: first, a fundamental dissatisfaction with globalizing tendencies and the resulting social and ecological problems, and second, the nearly impossible task of achieving change on a larger scale.

How can activists in El Raval put an end to low-cost flights? By squatting in empty apartments, they can only fight small-scale battles. A further challenge for the activist culture lies in its own attractivity. It would be interesting to know how many tourists take photos of banners that say “El Turisme Mata Els Barris” – “Tourism kills urban neighbourhoods”.

The different faces of tourism manifest themselves differently inside the barrio and are much more diverse than is apparent on the surface. It is important to realize that a lot of the positive economic developments in the barrio are happening because of tourism, and many residents have jobs connected with it, whether in a bar, as a street vendor, a tourist guide or with a building company. Several interviewees favour tourism because of its positive economic influence. Tourism has a huge impact on what it means to be local in a multicultural neighbourhood. It makes El Raval the biggest melting pot of Barcelona and adds to the image of a culturally vibrant neighbourhood. The plans of the Ajuntament de Barcelona to make the district internationally attractive have worked. Residents do not want tourism to disappear; but they fear getting pushed out of the barrio and feel left alone by the municipal authorities. Many inhabitants of Upper Raval have already had to leave their homes, and it seems it is only a matter of time before the same thing happens to communities in Lower Raval. For now, the motto is Raval No Resignat, “Raval does not resign”, painted on the biggest banner in the barrio directly next to MACBA.

How can activists in El Raval put an end to low-cost flights? By squatting in empty apartments, they can only fight small-scale battles. A further challenge for the activist culture lies in its own attractivity. It would be interesting to know how many tourists take photos of banners that say “El Turisme Mata Els Barris” – “Tourism kills urban neighbourhoods”.

The different faces of tourism manifest themselves differently inside the barrio and are much more diverse than is apparent on the surface. It is important to realize that a lot of the positive economic developments in the barrio are happening because of tourism, and many residents have jobs connected with it, whether in a bar, as a street vendor, a tourist guide or with a building company. Several interviewees favour tourism because of its positive economic influence. Tourism has a huge impact on what it means to be local in a multicultural neighbourhood. It makes El Raval the biggest melting pot of Barcelona and adds to the image of a culturally vibrant neighbourhood. The plans of the Ajuntament de Barcelona to make the district internationally attractive have worked. Residents do not want tourism to disappear; but they fear getting pushed out of the barrio and feel left alone by the municipal authorities. Many inhabitants of Upper Raval have already had to leave their homes, and it seems it is only a matter of time before the same thing happens to communities in Lower Raval. For now, the motto is Raval No Resignat, “Raval does not resign”, painted on the biggest banner in the barrio directly next to MACBA.

-

Literature

-

- (1) Barcelona Field Studies Centre (2019): El Raval. https://geographyfieldwork.com/ElRaval.htm (05.11.2019).

- (2) Barcelona Field Studies Centre (2019): The Social Cleansing of Southern El Raval. https://geographyfieldwork.com/ElRavalSocialCleansing.htm (05.11.2019).

- (3) Ajuntament de Barcelona (2017): Enquesta de Victimització 2017. Presentació de Resultas. http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/prevencio/sites/default/files/documents/informe-enquesta-victimitzacio-2017.pdf (04.11.2019).

- (4) Ajuntament de Barcelona (2018): Enquesta de Victimització 2017. Presentació de Resultas. http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/prevencio/sites/default/files/documents/enquesta-victimitzacio-2018.pdf (04.11.2019).

- (5) Barcelona.cat (2019): Estadísticas. https://www.barcelona.cat/ca/ (20.09.2019).

- (6) Carranco, R. (2019): Barcelona becomes Spain’s leader in rising crime rates. El País. https://elpais.com/elpais/2019/02/18/inenglish/1550485905_119074.html (05.11.2019).

- (7) Lisowska, A. (2017): Crime in Tourism Destinations. In: Research Review. Tourism, 27(1), 31-39.

- (8) Jauhiainen, J. (1992): Culture as a Tool for Urban Regeneration. The Case of Upgrading the ‘Barrio El Raval’of Barcelona, Spain. In: Built Environment, 18(2), 90-99.

- (9) McDonogh, G. (1987): The Geography of Evil: Barcelona’s Barrio Chino. In: Anthropological Quarterly, 60(4), 174-184.

- (10) Füller, H. and Michel, B. (2014): ‘Stop being a tourist!’ New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. In: International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304-1318.

- (11) Freytag, T. and Bauder, M. (2018): Bottom-up touristification and urban transformation in Paris. In: Tourism Geographies 20(3), 443-460.

- (12) Maitland, R. (2010): Everyday life as a creative experience in cities. In: International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(3), 177.

- (13) Guerilla Raval (2018): https://twitter.com/guerrillaraval?lang=de (05.11.2019).

- (14) Maitland, R. and Newman, P. (2009): World Tourism Cities. Developing tourism off the beaten track. London: Routledge.

- (15) Dennett A. and Song, H. (2016): Why tourist thirst for authenticity - and how they can find it. The Conservation. https://theconversation.com/why-tourists-thirst-for-authenticity-and-how-they-can-find-it-68108 (05.11.2019).

- (16) Wöhler, K. (2011): Veralltäglichung des Tourismus. In: Wöhler, K. (Ed.): Touristifizierung von Räumen. Kulturwissenschaftliche und soziologische Studien zur Konstruktion von Räumen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 44.

- (17) Airbnb (2019): EL Raval, Barcelona - Unterkünfte. https://www.airbnb.de/s/El-raval/homes?refinement_paths%5B%5D=%2Fhomes¤t_tab_id=home_tab&selected_tab_id=home_tab&source=mc_search_bar&search_type=filter_change&screen_size=large&checkin=2020-07-10&place_id=ChIJJSS_ffWipBIRQvCCQOH6ACY&hide_dates_and_guests_filters=false&checkout=2020-07-15 (04.11.2019).

- (18) Ajuntament de Barcelona (2019): Enquesta de Victimització 2017. Presentació de Resultas. http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/prevencio/sites/default/files/documents/presentacio_de_resultats_enquesta_victimitzacio_2019.pdf (04.11.2019).

- (19) Kagermeier, A. and Stors, N. (2017): Airbnb-Gastgeber als Akteure im New Urban Tourism: Beweggründe zur Partizipation aus Anbieterperspektive. In: Manuskript für Beitrag in Geographische Zeitschrift. Trier, 1-33.

- (20) Ajuntament de Barcelona (2019): El Raval. Ciutat Vella. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/ca/ (10.10.2019).

- (21) Saretzki, A. (2018): Städtische Raumproduktion durch touristische Praktiken. In: Zeitschrift für Tourismuswissenschaft, 10(1), 7-27.